Introduction

It seems clear that inequality in the United States has been growing. According to the World Bank website, the GINI index score for the US has risen from 38 in 1991 to 41 in 2019. It further seems that the mobility availability to people has become more stratified in decades past. Classical institutions that are created in order to mitigate these classic problems such as education (a tool of positive upward mobility) don’t seem to be solving the problem. Education spending in the US increased from 2.6% of GDP in 1953 to 5.9% of GDP in 2021. The rate of high school completion has skyrocketed over this time. Nevertheless, education, once thought the be the best available equalizer has not done so in a clear and effective way. Why is this, and despite the purported benefits, what role does education play in the problem?

Assumptions

In deciding to write a paper about a topic as dubious as endogamy and partner selection a number of simplifying assumptions have to be made and addresses. Any references to couples, partners, or spouses will refer to monogamous formal relationships which may or not include legal marriage. It will also, for the most, part assume in part or in totality a shared financial arrangement (not exclusively separate finances). Additionally, there are no other relevant groupings which might influence who is being selected as a partner by another (in reality, this is not the case as religion, race, and sexual orientation still play a large part in personal relationships).

These assumptions will provide a basic framework for analysis and will also help later on in our arguments of how certain relationships interact with each other. It is important to note that due to shared financial arrangements we see partnership or marriage as a vessel of upward economic mobility. This is because partners who decide to share household costs benefit from a financial synergy where the cost for two people to occupy and live in the same house is less than the cost for them each to live on their own. This leads to an increase in disposable income. This remaining income can be used for additional economic or financial increases such as wealth building (i.e. property, investments, etc.) human capital increases, or even just better quality of life. The more money couples make the wealthier we should expect those couples to be, on the whole.

Efficiency

In modern US society, we live in accordance with certain ancient models of efficiency and specialization of work. Few, in the 21st century, work in agriculture relative to the number of people who eat. Granted, the US does import a lot of food from international markets, however, this is not strictly relevant to the point. It is also generally true that the more education a person receives the higher their lifetime earnings will be. Again, despite large numbers of outliers this analysis captures the vast majority of modern Americans, and while the link between this education and earnings are much debated among economists (particularly whether it is causal or a form of signaling), it exists none the less. So, the question of inequality can be applied considering this understanding. If one group tends to earn at particular distributions, what would happen to inequality if these groups were endogamous?

What are Institutions?

For the purposes of this paper, we will adopt the definition of institutions provided by Douglas North in his paper… which considers institutions to be “…the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction. They consist of both informal constraints and formal rules.” (North, 1991) This is relevant and critical to this paper and underpins the assumption that people could, in principle, act in certain non-intuitional ways without violating laws, but most of the time choose not to.

By violating these norms there can be a wide array of negative consequences from minor disapproval of some to ostracism and being shunned by the wider society. It will become important later on those institutions can and do change over time and the mechanisms by which they do this is not entirely clear. There may be a tipping point at which time society begins to adopt a different attitude, or it may be something more formal such as Row v. Wade where it becomes “acceptable” because a legal entity has deemed it so, despite still being an issue of much controversy.

What is inequality?

In examining the role of endogamy on economic and political inequality we must first set out what endogamy in this context looks like. Historically, endogamy, in its various forms have been institutions imposed by governing bodies, laws, or norms. One examples of this type of institutions is marital practices among European nobility. Class governed who could marry whom and marrying outside of this institutional expectation often carries with it loss of status, removal from political power, and ostracism from society. Even as late as 1936 when British monarch Edward VIII abdicated to marry American socialite Wallis Simpson. This example clearly illustrates the formal nature of this endogamous relationship in an explicit way. However, the question remains, what about the non-explicit institutions which resemble what we see today.

In 1967 the United States Supreme Court in a ruling on Loving v. Virginia ruled that Interracial Marriage was protected under the 14th amendment adopted in 1868. Though legalized in the wake of this decision marriages of interracial couples remained at surprisingly low levels. As of 2010 interracial marriages accounted for only 15% of new marriages. Even with these low levels of marriages public opinion has increased to roughly 80% from approximately 5% in the 1950’s. It seems clear that there is something that keeps people from marrying outside of their racial groups. What could be the cause of this? One leading theory in political science notes that a history of redlining and exclusionary zoning has created racially homogenous neighborhoods in which people of difference races seldom interact. If people tend to interact only with a certain group of people, especially in the years people tend to enter into the partner selection process. If this is the case, we should expect to see higher levels of interracial marriage in more urban racially diverse areas, and less in rural racially homogenous areas. A 2017 PEW research article reported that in 2015 18% of new urban marriages were interracial compared to 11% in rural areas.

Returning to our analysis of education we can see strong parallels when we look at the available data about partner selection among education levels (include data from article). Clearly partners have a strong tendency toward similar educational attainment levels. This, last I checked was not enshrined in any law in the United States. Despite this, it appears regularly in available data. And not just at certain educational thresholds, but across the spectrum. The holder of a bachelor’s degree has roughly a 53% chance of marrying someone with a bachelor’s degree and only a 25% chance of marrying someone without one (the remaining 22% is a holder of a higher degree).

Like interracial marriage, some have speculated that this can be traced back to the distribution of encounters with potential partners. Because cohorts of students tend to develop social circles amongst themselves at their education levels, it is unlikely that you get high levels of educational diversification in these groups. Similarly, employers tend to hire and staff workers of similar educational disposition. So, if you are an eligible partner seeking person, and you encounter almost exclusively people of your own educational attainment status, one can see why it would be a natural pattern to emerge.

It is quite clear that this pattern does not come from some devious, malicious, or unnatural origin. Perhaps there are even deeper motivations of profit maximization we can see with partners selecting people who stand to have similar backgrounds, earn similar income, and share similar status (data from article).

The Choice of College (and, by extension, beyond)

Choosing whether to attend a college or university is a decision that most US high school graduates face. For some it is an extremely easy question to answer, one way or another. In these solutions we can find examples of discount costs at play.

Someone who wishes to opt out of higher education and enter the workforce is thought to have a relatively high discount value. Because of this, potentially higher future earnings are discounted down to a level below what they are earning upon entering the labor force right out of high school. On the other side, someone who chooses to attend school might have a lower discount value, and future earnings carry with them more weight than what they could earn at the outset. This provides another framework by which one could analyze partner selection and the relevant role of discount rates. This may play a key role, but one that is, except for this paragraph, unaddressed. This is something which has the potential to support or undermine my arguments and should be taken up in another project.

Literature Review

While this is not an extensively researched topic, there are a number of journal articles which provide a historical and analytic context in which to examine our topic. In one article we find an analysis of the historical importance of these endogamic class structures and the importance throughout history of the times these lines blur. They describe the drivers of social endogamy saying, “determinants of social-class endogamy can be clustered in various ways. A threefold division between individual preferences, third party influences and the structural constraints imposed by the marriage market is often used.” (Leeuwen, 2005) Further they touvh on one of the key concepts of endogamy and a significant problem we will face throughout the remainder of this paper, balance of probability in partner selection. “The opportunity to meet a potential spouse is often seen as factor explaining why people marry individuals similar to themselves. The marriage market is limited to certain contexts, for example to the neighborhood where one lives, and these contexts are to some extent already socially homogenous. Thus people end up marrying people similar to themselves even if they have no special desire to do so.” (Leeuwen, 2005)

In discussing specifically, the role of education related to social endogamy they go on to say that, “More importantly for endogamy, access to secondary and tertiary education – where participants might begin to look for a partner – has generally increased and in many countries become more universal, covering the whole spectrum of society to a larger degree than was formerly the case. One would expect this to lead to higher rates of exogamous marriage, the more so the older the age at which children are stratified into different school level.” (Leeuwen, 2005) This however does not consider the new and perhaps more pervasive form of endogamy we are now left with, our educational endogamy. Are we merely replacing one with another?

In another article by Lilyan A. Brudner and Douglas R. White we find a model set out to explain the stratification and codification of social classes through endogamous relationships. The model, based on an agrarian farming village in Austria, and focuses on some of the most important related issues such as “inheritance, wealth consolidation, and class formation in succeeding generations” (Brunder, 1997). They also note how individuals can be affected by circumstance that include them in one group or another saying, “Structural endogamy also demarcates lines of cleavage in a population, and segments siblings in the same family in terms of how their life courses differ.” (Brunder, 1997) This generational approach also sets the stakes for our current class dividing lines if indeed it is the case. Are we to end up like the Austrian farmers? They further note in their conclusion that “Structural endogamy does not require that every marriage in a relinked block be endogamous.” This is extremely relevant to the topic at hand as there are many cases of people marrying outside of the educational classes. A better question, and one informed by this research is, what are the tendencies, and what is the mobility? Are there institutions keeping children of the lower educational classes from advancing?

In an article focusing on the Caste based marriage structure of Punjab Pakistan researchers found that “social pressure, protection of family honor, geographic propinquity, and caste-based stereotyping as key social factors reinforcing endogamous marriages in the province.” (Safdar, 2021) As the process of mate selection is a traditional process executed by parents, elders, and generally not the participants in these cultures, we can see clearly that personal decision-making does not play a role in the outcome. If a marriage is to be based on mutually beneficial economic prospects, this is how it is likely to come about. This highly formal and institutionalized process is a much more defined endogamic relationship than our potential educational class structure, but we can still learn from it. Perhaps, by comparison, we can see that there largely aren’t issues with our current state of affairs. Perhaps, we have the ability to make a choice, and that choice may be influcenced by economic factors, but that doesn’t make it endogamy in the same way as the caste system. This seems correct, at least to a certain extent. It is true that the potential endogamy faced in the US is not the same as that the researchers described in this article, but that doesn’t mean it’s not endogamy. Again, we refer back to the idea of economic tendencies and the idea of institutions as informal practices innate in the culture. This is what we are discussing.

The Data

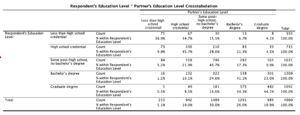

In an effort to answer this question I have collected data from the HNES regarding respondents’ education level and the associated partner education level. This data can tell us whether or not people do tend to be endogamous along these educational lines. Further if we can draw a relationship between education and income, we now have a direct path from an endogamous relationship to income inequality in the United States.

The data shows clear relationship among respondents and partners education level. Someone with less than high school credential has a 38.9% chance of partnering with somebody with the same educational level. They have over a 73.7% chance of partnering somebody who never attended college. This is compared to somebody who graduates with a bachelor’s degree who has an 11.3 chance of marrying somebody who has never attended college. The holder of a bachelor’s degree has roughly a 64.1% chance of marrying someone with a bachelor’s degree or higher. And an 88.7% chance of marrying someone who has attended college. The lines between partners in these education levels seem to be strict. This highlights the endogamous nature of these relationships.

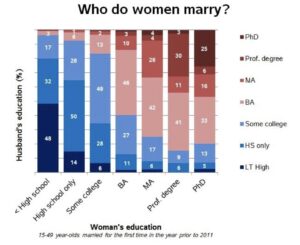

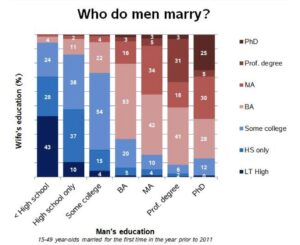

In another graph generated with different data, we can see a different but notable phenomenon. There are a couple of issues with these charts, including some of the factors that were used in the data collection. Among these are the age range, the use of only first-time marriages, and the assumption of heterosexual partnerships with a husband/wife relationship. Despite these issues, the data closely tracks my own and is effective at highlighting an important point. The slight differences in marriage patterns between men and women.

This data suggests that female cohorts tend to marry a larger percentage of men below their educational thresholds, that is, they marry men with less education. There are a few ideas about why this is. The most important explanation and the one that I believe to be the case is that due to the gender wage gap it is possible for women to marry down the education ladder but still up the income ladder as it is common for men with less education to make more money than women with more education.

Another possible explanation is that women tend to go back to school at a later time after getting married earlier. I could not find any data on this, but it would be another area for further research. What we can take away from this is that the tendencies we expect to see are less sever for women, but still exist.

Income and Education

It is a noncontroversial idea that the more education you get the more you will earn. While this is not a universal truth, it does encompass more than the average number of cases. In the data provided below we see that someone with a HS Diploma earns 60% of what a BA holder will make. Similarly, a BA holder will make 60% of what a Professional Degree holder makes. The outlier here is PhDs though this is likely due to people in academia who tend to earn less than those with Professional degrees in the public sector despite it generally being less schooling.

Making The Case

So, if we see that there are indeed relationship lines based on these endogamic relationships and we see that people earn income based on educational attainment we can draw the conclusion that these couples tend to earn similar amounts. This limits the extent to which someone at a lower education level can marry up the income ladder. While there will naturally be some synergistic benefit from a dual earner household, this is diminished by each part of the couple earning marginally less then their better educated counterparts. This naturally gives rise to a class-based system in which people tend to marry others within their own education levels. This reduces the chance for more equitable economic outcomes distributed through the free market of relationships. Now that we have examined the relationships between the core concepts in this paper, we can turn our attention to matters of policy and correction of the issue, if indeed it is an issue.

Classic responses to this issue

We now turn our attention to issues of policy. We will begin with a brief exploration of the classic response to educational inequality and by extension the outcomes this inequality brings about. The classic policy response to this is an increase in funding to education, which stands to move more people into the higher earning brackets and increases the upward mobility because of this. If the problem stems from the fact that there are educational losers and winners, lets solve it by pushing those in the former category into the latter. This, in principle, would help those who otherwise would not pass that educational threshold (whether it be HS, BA, or MA), and reap the benefits of having done so.

This response, however, doesn’t seem to solve the problem of cohort building and social groups, which are basic features of humanity as discussed in Leeuwen. Instead, this solution seeks to minimize the bottom of the distributions, thereby bringing up some in the worst-off group. This is akin to a Rawlsian conception of a just society. When combined with our understanding of economics and discount values as they relate to education this does not paint the clearest picture. The policy most associated with this thought is public education. By spending additional money to educate the bottom of the distributions we can move people into higher earnings brackets. While this works in principle, it enevitably just makes the threshold of the elite more unachievable. If 100 years ago you needed a BA to be “successful”, then by comparison today you would need a PhD. With more poured into the bottom of the distribution 100 years hence perhaps a small collection of PhDs.

Better responses to this issue

In Economics, nudges have become a topic of much discussion since the landmark work done by Thaler who won a Nobel prize in Economics for the work. A nudge is a change to a policy, practice, or institution that is subtle and often inexpensive in nature that has a large effect on a problem or concern. For example, issues of low organ donor participation might be corrected by moving from an opt-in to an opt out. It is just a simple change of whether to tick the box to participate or tick the box not to participate, but this has consistently had a dramatic effect on participation. In examining our issue of inequality due to natural and innocent practices, one might wonder if there is a nudge practice that might mitigate the problem.

One example might be to generate more situations for people of typical eligible age to interact with one another. Certainly, something as radical as conscription, or mandatory military service seems a bit far, but forcing people of different backgrounds into a common situation and making them get to know each other sounds a lot like a college campus, high school classroom, or even an office at a firm with the exception that people aren’t sorted into education levels with conscription.

Perhaps There Isn’t a Response

While the discussion of this issue is analytic in nature, it is important to remember that we are ultimately discussing who someone decides to marry, and this generally involves an element of love. Is this something the government should be creating policy about? Is this something that people would tolerate policies about?

Conclusion

We began this discussion by asking a question. What role does education play in endogamy in the US? After consulting the literature, we can see that there is a documented history of social endogamy relate to education. This however was backed mainly by theory, and not by empirical data. I next presented data which highlighted the relationship between an ANES respondent’s education level and that of their partner as well as separate data which highlighted similar data split based on gender. After analyzing the relationship with data from the Bureau of Labor statistics we can see that earnings should track along the same lines as these spousal cleavages.

We have therefore examined the role of education in the building of a new form of class-based endogamy. We have seen that the strong relationship between education and income when combined with the use of marriage as a tool of upward economic mobility in building these new classes. We have also seen that despite many counterexamples we see trends of these relationships in the classes. This leaves us with the conclusion that indeed education is a factor in an endogamous institution which leads to inequality.

The result of this, however, seems inescapable. While all of the above seems apparent, we aren’t left with a clear sense of whether or not it is a problem that needs a solution. If a solution were available, such as education budget increases, conscription, etc.

Bibliography:

- Brudner, Lilyan A., and Douglas R. White. “Class, Property, and Structural Endogamy: Visualizing Networked Histories.” Theory and Society 26, no. 2/3 (1997): 161–208. http://www.jstor.org/stable/657926.

- Leeuwen, Marco H.D. van, and Ineke Maas. “Endogamy and Social Class in History: An Overview.” International Review of Social History 50 (2005): 1–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26405547.

- Mare, Robert D. “Change and Stability in Educational Stratification.” American Sociological Review 46, no. 1 (1981): 72–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095027.

- North, Douglass. 1991. “Institutions.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5(1): 97-112.

- Safdar, M. R., Akram, M., Sher, F., & Rahman, A. (2021). Socioeconomic Determinants of Caste-based Endogamy: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 8(2), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/697